Expanding the potential of the quantum bits that underpin quantum computing

Paving the way for a future in which information flows between electrons and light

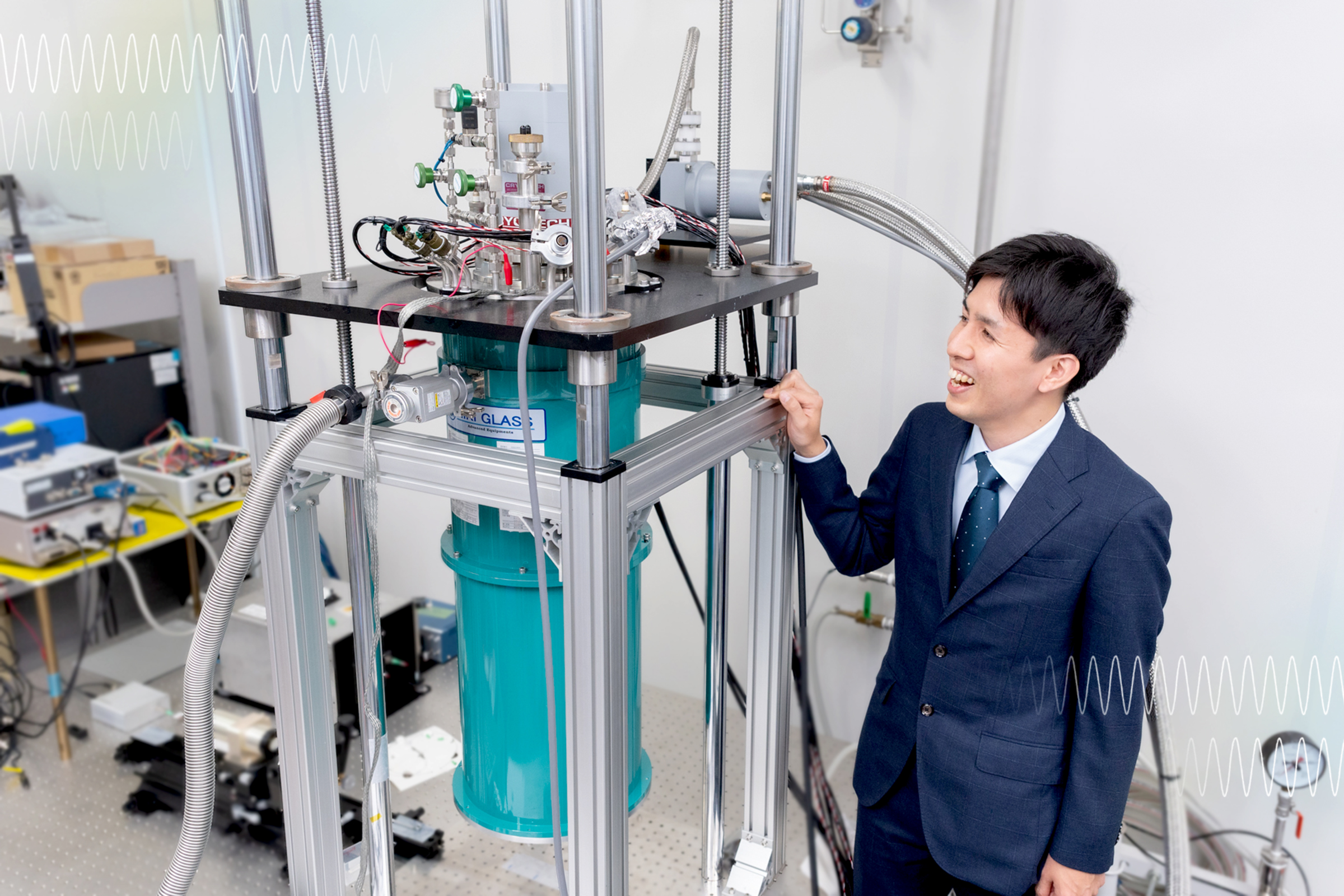

Quantum computers are developing rapidly in countries around the world. They are believed to have the potential to achieve computation speeds up to 100 million times faster than conventional computers. As an example, this would allow calculations that currently take over three years on a supercomputer to be completed in a single second. Quantum bits are a critical and foundational component of quantum computers, and Associate Professor Kazuyuki Kuroyama of the Institute of Industrial Science, The University of Tokyo, has achieved noteworthy results in his research aimed at expanding their potential. His research focuses on enabling the transfer of information between different types of quantum bits. What does this entail, and what possibilities does this research open up? We asked Kuroyama.

Toward the realization of quantum computers

Quantum computers, which are expected to surpass conventional computers by orders of magnitude in speed, already exist on a very small scale for specific applications. However, none are in wide use. In response to this situation, Associate Professor Kuroyama is researching a technology that could play a crucial role in the development of general-purpose quantum computers. Taking a closer look into his research, we found the title of a lecture he delivered at the Japan Society of Applied Physics in 2023:

“Ultra-Strong Coupling: Observation of the Ultimate Interaction Between Light and Matter in a Single Optical Resonator”

What exactly is he researching? We asked Kuroyama to explain the nature of his research—which is a bit difficult to infer from the technical terminology used—in the simplest terms possible.

What is hybrid quantum conversion in the context of converting quantum bits?

Kuroyama explained that the key to quantum computers’ incredible speed lies in quantum bits, or qubits, which correspond to bits in classical computing. However, unlike conventional bits, which must take on the value of either “0” or “1,” qubits are able to exist in a superposition in which they possess the values of both “0” and “1” simultaneously.

While the unique properties of qubits are what make quantum computing so astonishingly fast, devising means of developing (and implementing) qubits poses the greatest challenge in the development of quantum computers. That is to say that the most difficult aspect of quantum computer development is determining which physical systems to imbue with qubit properties.

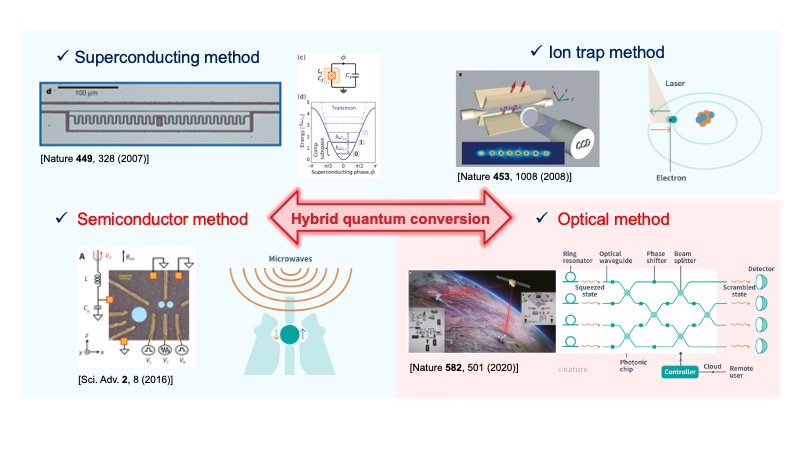

Several methods for realizing qubits are currently being explored, with significant research progress being made in the superconducting method and the ion trap method. The superconducting method realizes qubits using a type of electrical resonance circuit cooled to extremely low temperatures, while the ion trap method makes use of ions arranged in a vacuum using an electric field. However, each method presents its own challenges. As an example, the superconducting method faces integration limitations due to the relatively large size of each qubit. As such, researchers continue to search for alternative implementation methods, and Kuroyama’s work is related to two methods distinct from the above. One (known as the semiconductor method) realizes qubits using electrons confined within extremely small semiconductor crystals called semiconductor quantum dots. The other (known as the optical or photonic method) uses photons—light particles—as qubits.

Methods for implementing quantum bits Credit: Kazuyuki Kuroyama Laboratory

Kuroyama explained, “I research ways of transferring quantum bit information between these two methods. In other words, my research focuses on a method called hybrid quantum conversion, which enables the bidirectional transfer of information between photons used as qubits and electrons confined within semiconductor quantum dots used as qubits.”

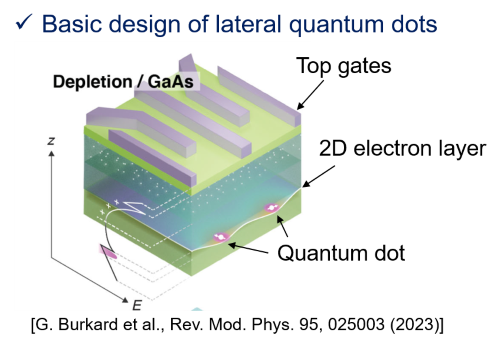

Individual electrons can be confined within semiconductor quantum dots a few hundred nanometers* in size

*A nanometer is one millionth of a millimeter.

Credit: Kazuyuki Kuroyama Laboratory

The significance of converting qubits lies in the ability to leverage the advantages of each type of qubit. For example, combining the semiconductor method, which facilitates miniaturization and integration, with the optical method, which is highly compatible with communication technologies, would provide the advantages of both simultaneously. Furthermore, hybridizing—or integrating—different types of qubits could also provide access to new functions that are unavailable when the bit types are used individually. The title of the aforementioned lecture “Ultra-Strong Coupling: Observation of the Ultimate Interaction Between Light and Matter in a Single Optical Resonator” refers to the exchange of information between electrons (matter) and light. Kuroyama successfully demonstrated this in an experiment conducted in 2023, marking a crucial step toward realizing this form of hybrid quantum conversion.

Working to enable information to flow between individual photons and electrons

Let’s delve a bit deeper into this research.

Various studies have already explored quantum conversion between electrons and photons in semiconductor quantum dots, so this field is not entirely new. What then sets Kuroyama’s research apart? The significant distinction lies in the phrase “using a single optical resonator” from his lecture.

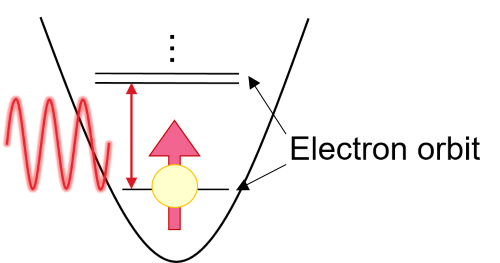

Kuroyama is developing a quantum conversion method that makes use of a terahertz-band optical resonator. Specifically, it generates a hybrid state by strongly coupling photons with terahertz-band frequencies to electrons. Quantum dots have a shell structure similar to that of atoms, and the energy levels of their electron orbitals typically align with terahertz-band electromagnetic waves. Therefore, using terahertz-band electromagnetic waves should enable more efficient quantum conversion than conventional methods. However, previous approaches using terahertz-band optical resonators have typically involved setting up arrays of dozens or hundreds of such resonators coupled to groups of thousands or even tens of thousands of electrons within a semiconductor, and using light to observe the averaged signal from the multiple resonators. However, when applying optical resonators to quantum dot systems, conducting observations requires coupling a single optical resonator with a single electron confined within a quantum dot. Kuroyama’s research is both novel and noteworthy for first observing the hybrid state of multiple electrons in a semiconductor with a single optical resonator (as presented at the Japan Society of Applied Physics in 2023, https://www.iis.u-tokyo.ac.jp/en/news/4356/), and then reproducing this between a single optical resonator and a very small number of electrons in a quantum dot (https://www.iis.u-tokyo.ac.jp/en/news/4441/).

Inside semiconductor quantum dots, electrons occupy quantized orbits, similar to those in atoms, and in the case of quantum dots, the energy spacing between their orbits aligns with the energy of photons in the terahertz band. Therefore, quantum conversion using a terahertz-band optical resonator and semiconductor quantum dots promises to be more efficient than conventional methods. Credit: Kazuyuki Kuroyama Laboratory

“The signal from multiple optical resonators is an average of the information from each resonator, and quantum information is lost in the process. That makes such an approach unsuitable for use in quantum computing, in which the information of each individual qubit is crucial. Therefore, there has been strong demand for a means of quantum conversion between individual electrons and photons confined by a single resonator. I feel that achieving something very close––even using terahertz-band electromagnetic waves––is a significant advancement.”

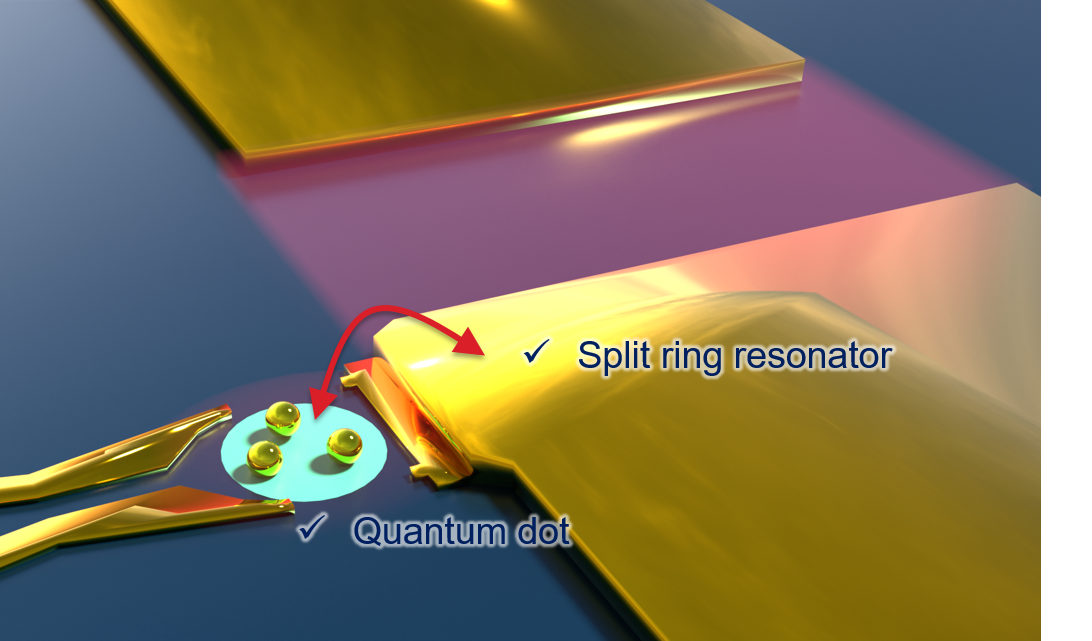

An illustration of an experiment in which a quantum dot is coupled to an optical resonator. Multiple electrons within the quantum dot exhibited strong coupling with the optical resonator (indicating that the coupling between the optical resonator and the electrons leads to hybrid quantum conversion between the two).

Credit: Kazuyuki Kuroyama Laboratory

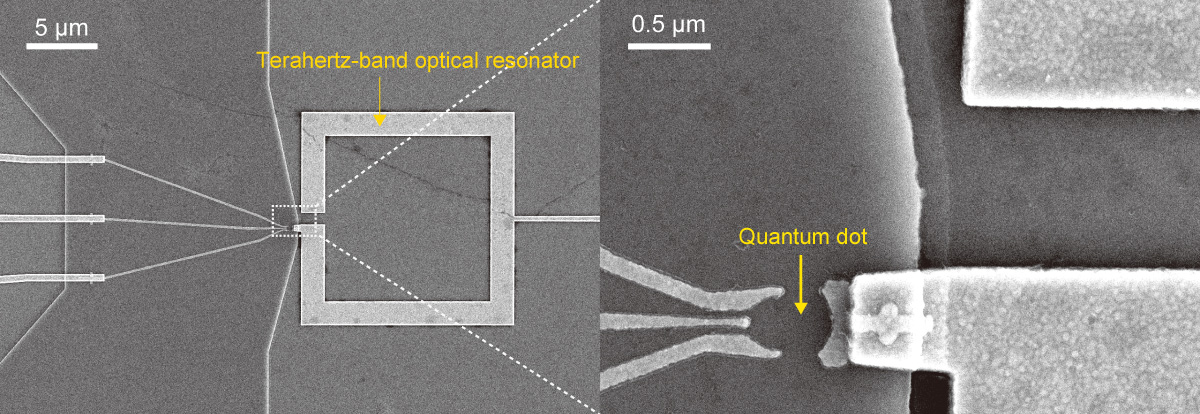

A photograph of a sample in which a quantum dot fabricated on a semiconductor substrate is coupled to a terahertz-band optical resonator. The zoomed-in photo on the right shows where the quantum dot forms between the three electrodes and the resonator.

Credit: Kazuyuki Kuroyama Laboratory

When looking again at the necessity of such quantum conversion—specifically, hybrid quantum conversion—it is clear that one key reason is to develop quantum communication, enabling the transmission of quantum information over long distances. Quantum communication in this case does not necessarily entail long-distance communication. It can also include transmission over just several hundred micrometers on a semiconductor chip. Technology enabling quantum communication on semiconductor chips is considered a particularly essential in the large-scale development of quantum computers. Further advancements in this research into hybrid quantum conversion using terahertz-band waves will allow electromagnetic waves to form quantum connections between multiple quantum dots positioned far apart on a semiconductor chip. This technology for remotely coupling semiconductor qubits is expected to pave the way for the realization of practical-scale semiconductor quantum computers in the future.

Unveiling new possibilities for the future by exploring the unknown

While this research may seem quite complex, technology for transmitting information over long distances by encoding it onto an electron and converting it into light could significantly impact the future of all of us. In conclusion, we once again asked Kuroyama what makes this research so fascinating.

“I began research involving semiconductor quantum dots while in my graduate school master’s program, and I remember being deeply impressed at the time by the fact that it was technically possible to confine individual electrons—extremely tiny particles—inside semiconductor quantum dots, and even more so by the ability to directly observe their behavior. Also, my fascination with research was renewed when I realized that even a well-studied subject like semiconductor quantum dots can still give rise to new phenomena when combined with technologies from unexplored fields, such as terahertz-band waves. I understand that this research sounds complex, but I would be delighted if you would continue to follow its future developments with interest.”

Related Article> Communing with Nothingness

Related Article> Advancement in transmitting quantum information for high-speed information processing

Comments

No comments yet.

Join by voting

How did you feel about the "Possible Future" depicted in this article? Vote on your expectations!

Please visit the laboratory website if you would like to learn more about this article.

Share