The Disaster Management Field Guide, Providing Guidance at the Frontlines of Disasters

A model for promoting disaster management amid complex social and emotional challenges

“Let me check your breathing.” “I’m sure that you’re in pain, but you’re going to be okay.” These were comments made by participants in a training session at the Disaster Management Training Center (DMTC), Institute of Industrial Science, The University of Tokyo. The Disaster Management Field Guide is designed for hands-on training that closely simulates real-life scenarios as well as for use at actual disaster sites. We spoke with Associate Professor Muneyoshi Numada of UTokyo-IIS, the creator of the Field Guide.

Applying the Unique Perspective of a Consultant

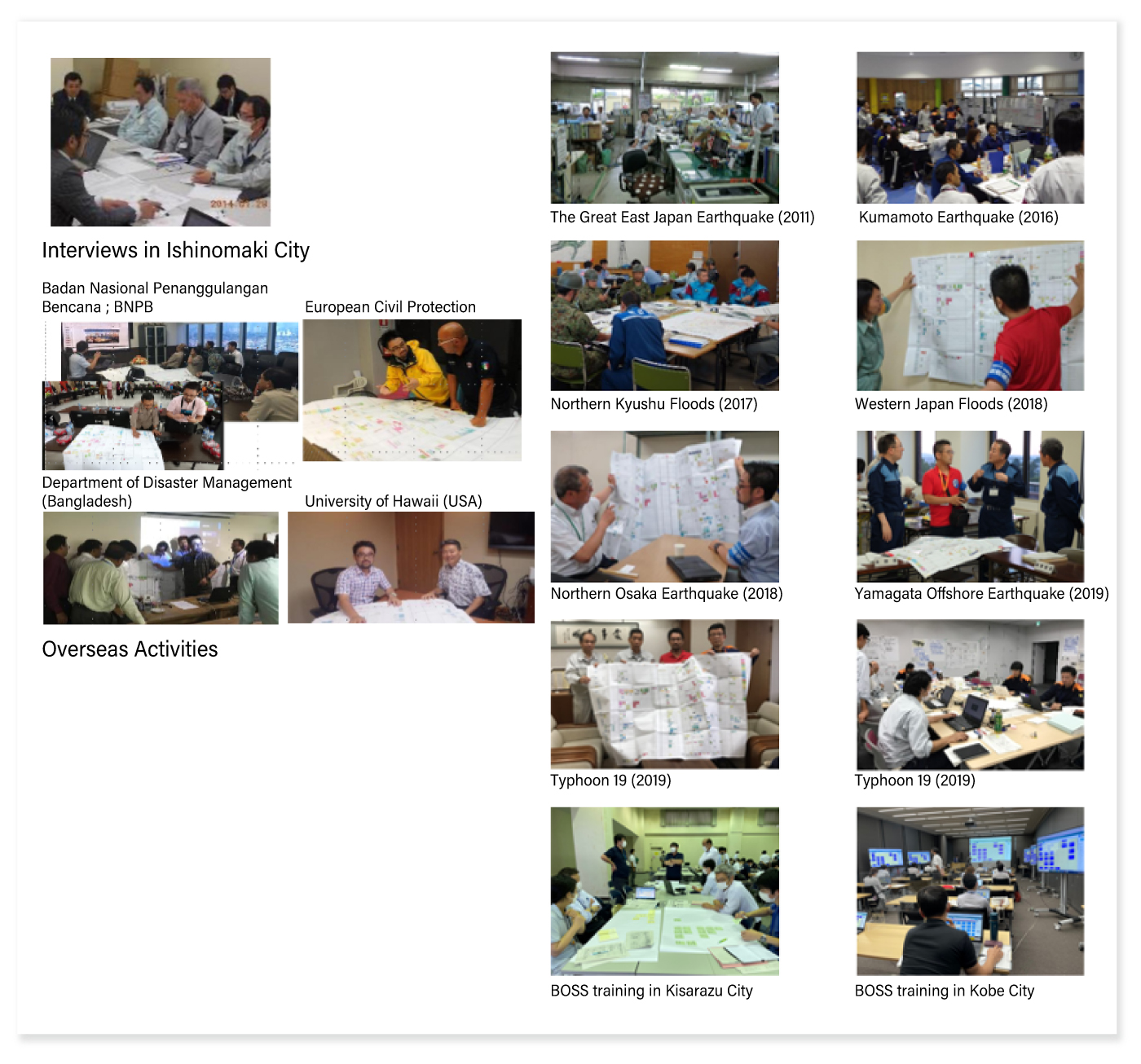

The Great East Japan Earthquake disaster (2011), Kumamoto Earthquake disaster (2016), Central Italy Earthquake disaster (2016), Northern Kyushu Floods disaster (2017), Western Japan Floods disaster (2018), Northern Osaka Earthquake disaster (2018), Hokkaido Eastern Iburi Earthquake disaster (2018), Yamagata Offshore Earthquake disaster (2019), and Typhoon Hagibis disaster (2019)…

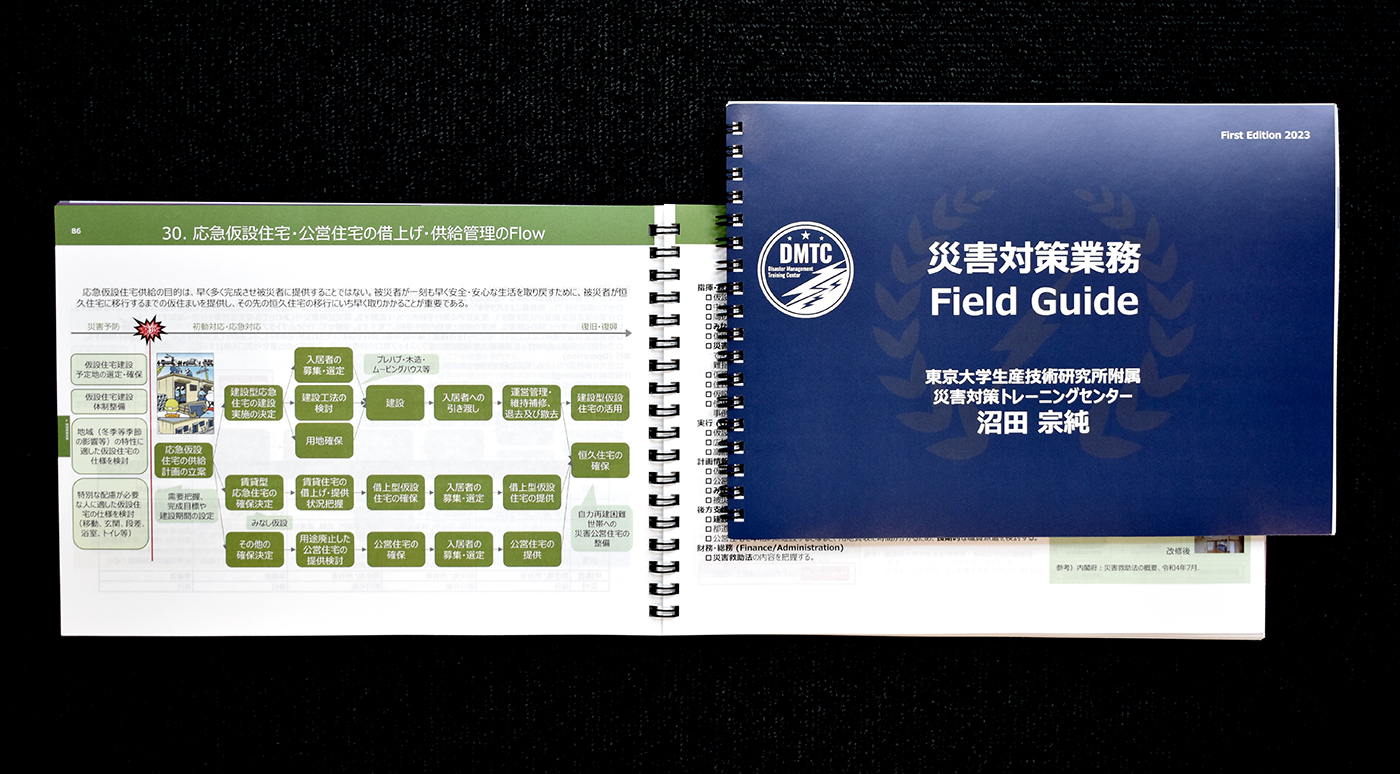

There now exists a single handbook that brings together the insights and lessons learned by those who have responded on-site to these and other disasters––the Disaster Management Field Guide. Associate Professor Numada, a specialist in disaster management process engineering at the DMTC, UTokyo-IIS, developed it.

Field Guide to Disaster Management Activities.

Numada, a graduate of the University of Tokyo, majored in civil engineering and earned a PhD degree in engineering, with his research focusing on landslides. After graduation, he joined a private consulting firm, where he helped streamline operations across various industries and projects. Then, one day, he overheard someone mention that Japan’s disaster management efforts were being executed poorly.

“In Japan, municipal government officials form the core of disaster management headquarter personnel. However, the problems inherent in this structure have long been known, as staff members are reassigned every few years, making it difficult to retain disaster management professionals. Back in university, I had been involved in basic research, but hearing about this issue made me realize that I instead wanted to do work that protects people more directly.”

Upon returning to UTokyo as an assistant professor, he immediately set out to create a comprehensive map of the disaster management functions and tasks. In 2009, he began drawing on various regional disaster prevention plans as a means of identifying the overall framework.

“To begin with, no comprehensive overview had been compiled, which made it hard to see where the challenges and issues were hidden. My very first desire was to create a framework enabling people at disaster sites to identify what tasks need to be addressed immediately and to share that information with others.”

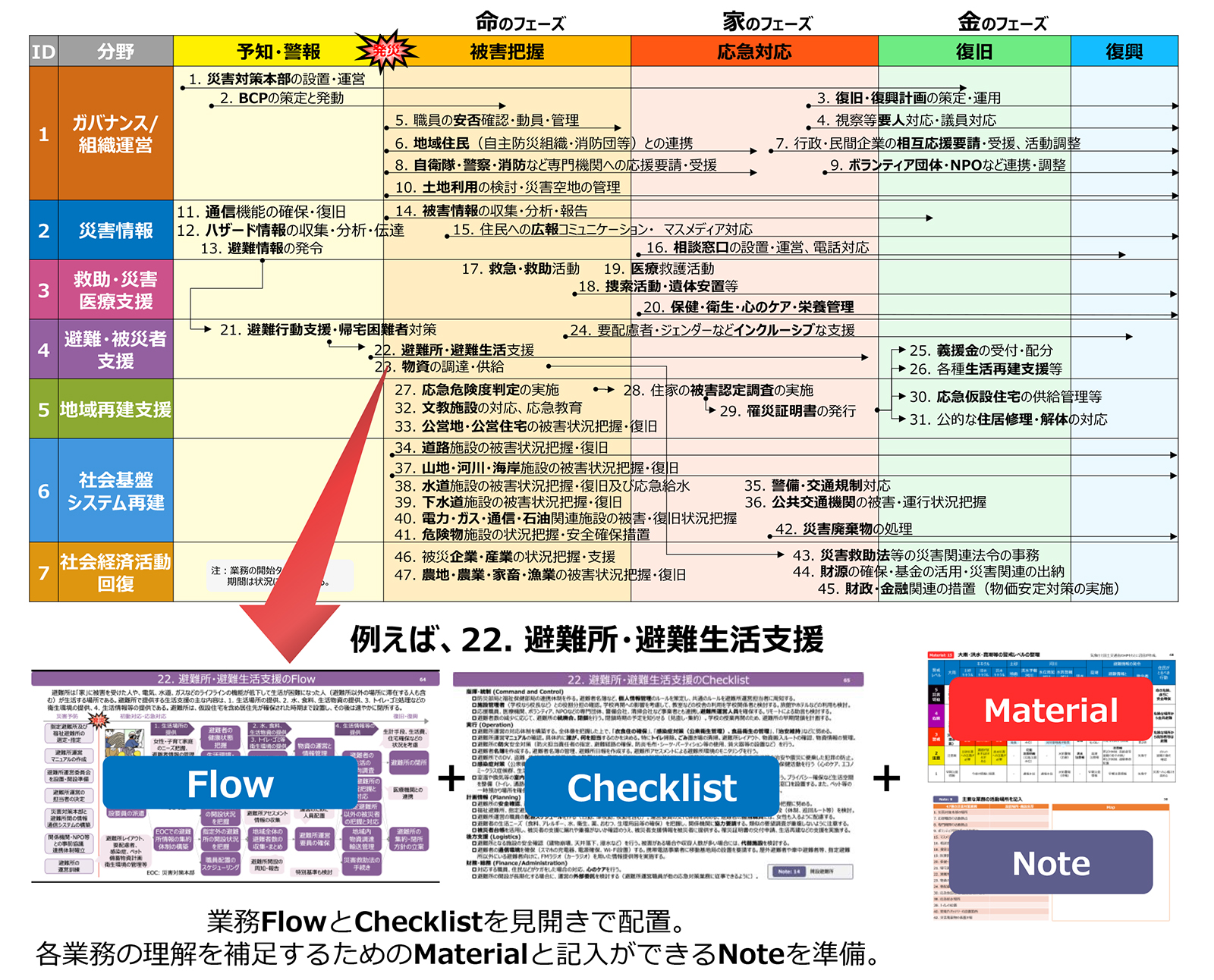

The 47 Tasks Required During All Disasters

A large map displayed on the wall provides a visual representation of the key 47 disaster management tasks that have been identified, beginning with the establishment of a response headquarters. It is organized both chronologically and by category. The tasks are grouped into eight categories: Disaster Management Principles, Governance and Organizational Management, Disaster Information, Rescue and Disaster Medical Assistance, Evacuation and Victim Assistance, Community Reconstruction Assistance, Restoration of Social Infrastructure and Systems, and Recovery of Social and Economic Activities. How, then, was this overview developed?

“Putting the entire disaster management process into words requires an extensive base of knowledge relating to disaster sites, including local geological structures and buildings through to an understanding of human psychology and social systems. I learned more about evacuation shelter operations, supplies, and related matters. When it came to aspects such as roads and other civil engineering elements, my background in geotechnical engineering—specifically, studying landslides, liquefaction, and similar sediment-related disasters—proved especially valuable. That sort of engineering knowledge also applies to infrastructure, lifelines, and buildings.”

Earthquakes, typhoons, heavy rains, and all other types of natural disasters were taken into account. Numada explained, “This is because the initial response is fundamentally the same, regardless of the type of disaster. I realized that standardizing those first steps and clarifying what to do would make it easier for even first-time responders to take action.”

Part of a map showing the overall picture of disaster management. The horizontal axis shows time, the vertical axis shows organization names, and “when, who, and what” are color-coded for each task.

Then, the Great East Japan Earthquake Struck…

On March 11, 2011, Numada was at the Kanagawa Prefectural Government Office for a meeting regarding his map. It was scheduled to begin at 3:00 p.m., and as he was waiting for it to commence, the Great East Japan Earthquake struck.

“I was immediately brought into the disaster management headquarters for Kanagawa Prefecture. I remember holding up the map and explaining the response procedures to members of the media. Later, thanks to the long-term assistance of Yabuki Town, Fukushima Prefecture, and Ishinomaki City, Miyagi Prefecture, I was able to interview many of the officials who had been directly involved in responding to the disaster. Through this process, I continued to refine the first version of the map. I made further refinements through training programs led by the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications and the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism, and well as through insights from actual disaster management sites, including Nishihara Village and Kumamoto City, Kumamoto Prefecture, following the Kumamoto Earthquake in 2016; Asakura City following the Northern Kyushu Floods in 2017; and Kurashiki City following the Western Japan Floods in 2018.”

Numada further explained, “As I listened to the experiences of government officials, I became even more determined to support them.”

“Disaster responders are often pushed to their physical and emotional limits. Some head to the front lines of a disaster even after losing their family members or friends. It’s a life-threatening and truly grueling undertaking. These responders are often disaster victims themselves, yet they’re also frequently the ones who bear the brunt of the fear and frustration vented by other citizens with nowhere else to turn. Some end up leaving their jobs, and others are pushed to the point of mental collapse. I want to do whatever I can to protect these people.”

These individuals are obligated to confront disasters both as private citizens and as public servants. To help disaster victims–including the responders–regain a sense of normalcy as quickly as possible, Numada used this map as the foundation for the Disaster Management Field Guide, a handbook laying out disaster management operations in greater detail. He is also committed to education and outreach, using these tools as key resources.

Practical Training Programs at the University of Tokyo

At the DMTC, led by Numada, educational programs have been developed that use the map and Field Guide as core teaching tools. The DMTC offers basic-level programs covering topics such as disaster management theory and disaster science, as well as more advanced programs, including training on how to operate a disaster management headquarters, providing participants with hands-on experience.

The programs are primarily for government officials, employees of private companies involved in public administration, leaders of autonomous disaster prevention organizations engaged in mutual aid, and members of volunteer groups. Participants work in groups, rapidly sharing information as they work to address a scenario based on a past, real-life situation. So far, the programs—both basic-level and advanced—have welcomed over 1,000 participants, including those from South Korea, Kenya, and other international locations.

The map is put up in the disaster management headquarters. Each team member then turns to the page in the Field Guide that covers the task they have been assigned. The relevant page provides specific procedures, checklists, and key considerations for each task. The goal is for participants to maintain an up-to-the-minute awareness of both the overall situation and the progress of their task, even as conditions continue to shift from moment to moment, and then to effectively reflect that awareness in their management.

From “Field Guide to Disaster Managememt Operations”

“When disaster strikes unexpectedly, it’s only natural to feel lost and overwhelmed. I hope that hands-on experience, even if only simulated, will provide people with both the knowledge and confidence they will need. In real-life response efforts, things often don’t go as planned, no matter how rationally you try to proceed. The processes of preventing and recovering from disasters are intricately entangled with a variety of social issues and involve conflicting values, giving rise to emotional tension. I hope this Field Guide will serve as a tool that remains even under such challenging circumstances, facilitating communication and helping people move forward together.”

A Vital Foundation for Society, Though It May Not Bring Us Happiness

Numada is also developing the Business Operation Support System (BOSS), a disaster management process management system that systematizes the Disaster Management Field Guide. It incorporates checklists into digitized processes to provide more in-depth information. BOSS has been adopted by 60 government bodies across Japan, including Kumamoto Prefecture, Tokushima Prefecture, Saitama Prefecture, Wakayama Prefecture, Kobe City, Kawasaki City, and Kisarazu City.

“The first goal is to establish the eight categories and 47 types of disaster management tasks outlined in the Disaster Management Field Guide as the standard model across Japan, to enable government bodies, businesses, and autonomous disaster prevention organizations to respond with a shared understanding. Preferably, having a framework that distills disaster management processes down to their essential elements will enable each organization to develop a customized disaster management manual—one that addresses all key points while also reflecting own unique local conditions. I also hope that this tool will make Japanese expertise in this area available for use in disaster management efforts overseas.”

The Field Guide is for those at the heart of disaster management efforts, protecting the lives of countless others. Even now, Numada continues his work with dedication and resolve.

How can we as individuals do our part in disaster prevention? While we may intellectually understand its importance, we tend to put off taking any action…

“Disaster prevention isn’t something that brings us happiness. It doesn’t make our daily lives more enjoyable or fulfilling. Ideally, we would be able to live our entire lives without ever needing to face such circumstances. However, a disaster could strike one day without warning, upending our lives––or even taking away someone dear to us. Ultimately, it comes down to whether or not we can protect ourselves and the people we care about. That being said, however, thinking about disasters and how to prevent them daily can be overwhelming. That’s why I would like for people to consider the topics of disaster prevention and response from time to time, as a small but meaningful addition to their daily lives.”

Survey of affected areas during the 2016 earthquake in central Italy

Main visual: Comparing disaster preparedness operations in Japan and Italy with Civil Protection Department staff during a survey of the affected areas after the 2016 earthquake in central Italy.

Credit: Muneyoshi Numada Laboratory

Related Links> Disaster Management Training Center

Related Links> Civil Protection Department

Comments

No comments yet.

Join by voting

How did you feel about the "Possible Future" depicted in this article? Vote on your expectations!

Please visit the laboratory website if you would like to learn more about this article.

Share