Understanding the mechanisms of the human brain by building and connecting tissues

Complex activity of brain organoids interconnected via axons

In recent years, a great deal of research has been conducted on creating organ models known as organoids. Organoids are produced by differentiating stem cells or iPS cells into the cells of a target organ while culturing them in three dimensions, thereby partially replicating cell-to-cell interactions and certain functions of the organ. Brain-mimicking organoids have also been developed and are drawing attention as a new approach to neuroscience research. At the Institute of Industrial Science, The University of Tokyo, Professor Yoshiho Ikeuchi is taking an inventive approach to brain organoid research, employing unique methods to uncover the secrets behind the intricate workings of the human brain.

Giving rise to intricate network functions

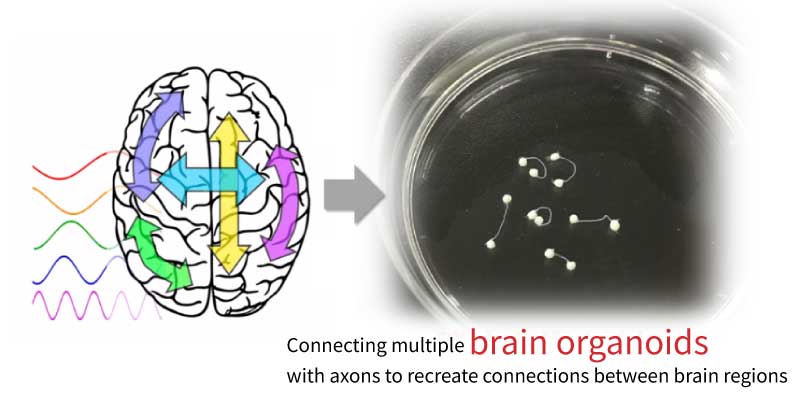

Credit: Yoshiho Ikeuchi Laboratory

What do you see in this photograph? You might think they are newly sprouted plant seed—or perhaps some kind of fungus. In fact, this is a “connectoid”—a structure formed by linking two cerebral organoids grown from human iPS cells through neural projections known as axons. The somewhat gentle appearance illustrates the innovative nature of Ikeuchi’s research.

Brain organoids are not merely aggregates of neurons. Notably, they have complex internal structures, and in some regions, neurons can be observed exchanging electrical signals with one another—just as they do in an actual brain. In the human brain, however, complex functions arise from the interconnections between distinct regions, such as the cerebral cortex, hippocampus, and cerebellum, through axons that enable continuous information exchange. Many brain organoid studies to date have produced models that mimic only specific brain regions. While these have allowed observation of internal neuronal activity, they could not replicate interactions between different regions. The connectoid created by Ikeuchi and his team is an innovative attempt to break through this limitation.

“In our laboratory, we developed a method to spatially control extension of axons from organoids. Although we first began researching motor neuron tissue, we later considered whether the method could also be applied to cortical neurons as well. We succeeded in connecting two organoids by placing them in a specialized device and controlling the direction of axons to make them extend toward each other. This partially resembles our own brain, where the right and left hemispheres are connected via the corpus callosum.”

Credit: Yoshiho Ikeuchi Laboratory

Connectoids displayed more complex and strongly synchronized neural activity than single brain organoids or directly fused organoids. Moreover, the researchers observed that, when bundles of axons were stimulated, neural activity remained elevated for a period of time afterward. This response represents a form of plasticity—the ability to alter activity based on prior stimuli—essentially serving as a model of short-term memory. This suggests that connectoids may exhibit functions more closely resembling those of the human brain.

These findings were a great surprise even to Ikeuchi himself.

“It’s truly fascinating to see that connecting brain organoids through axons brings their activity one step closer to that of the human brain. I had long wondered why the human brain is divided into right and left hemispheres connected by axons. It seems clear now that the interplay between separate yet interconnected clusters of neurons is essential for brain function. The way information races through the brain along intricate pathways may well be the very basis of its complex activity.”

Ikeuchi says, “Going forward, we plan to connect organoids derived from different regions of the brain to further our experiments.” He believes that creating a variety of connectoids will yield important insights into better understanding the brain as an integrated system.

Pursuing life science research with an engineering-based approach

Ikeuchi began his work on creating connectoids using specialized devices through collaboration with researcher Jiro Kawada, who at the time was studying microfluidic devices—systems capable of controlling fluid flow and cellular behavior within extremely small channels and tunnels—under Professor Teruo Fujii, who worked at UTokyo-IIS.

“Connecting cerebral organoids with one another requires controlling axons in three dimensions, and attempts to apply conventional two-dimensional culture techniques did not work well for us. So, we decided to take a different approach. By designing a simpler device and carefully optimizing factors such as the width and depth of the guiding grooves and the culture conditions to encourage axons to extend naturally, we succeeded in creating brain organoids connected via axons.”

Although Ikeuchi makes it sound simple, the techniques required to create connectoids is not something other research groups can easily come up with. After spending many years cultivating axons, he has gained an intimate understanding of their characteristics. By combining this expertise with the engineering approach introduced by Kawada, they were able to establish a technique unlike that of any other researcher.

In reflection, Ikeuchi said, “I think I may have always wanted to be an engineer.”

“From 2007 to 2014, I conducted research in the United States on the roles of proteins in neural morphogenesis and development. Meanwhile, in Japan, Professor Yoshiki Sasai achieved a breakthrough in 2008 by creating three-dimensional neural tissue from ES cells—a pioneering step that laid the foundation for today’s brain organoids. Hearing that news while in America gave me the sense that biology was rapidly transforming, and I found it incredibly fascinating.”

Ikeuchi returned to Japan in 2014 and established his own laboratory at UTokyo-IIS. He had long been considering how to shape his path as a researcher, and his encounter with Kawada became the catalyst that opened up new possibilities. Integrating engineering techniques into research on brain organoids derived from human cells made it possible for connectoids to capture phenomena that could otherwise never be directly observed in an actual brain, opening a pathway into the uncharted realms of neuroscience.

The future of neuroscience will transform medicine and computer technology

What does the future of connectoid research hold? Looking ahead, Ikeuchi envisions possibilities branching out in many different directions.

“There are many possible directions for the future of this research, but I hope that it will first lead to medical applications. For diseases that involve higher brain functions, it is difficult to evaluate the effects of drugs through conventional cell experiments, and even studies using animal models often leave many questions unanswered. If we can develop connectoids that replicate human brain functions, it will allow us to evaluate the efficacy of newly developed drugs with far greater accuracy. Moreover, if we can create connectoids from patients’ own cells for research, it may become possible to uncover the underlying mechanisms of their diseases.”

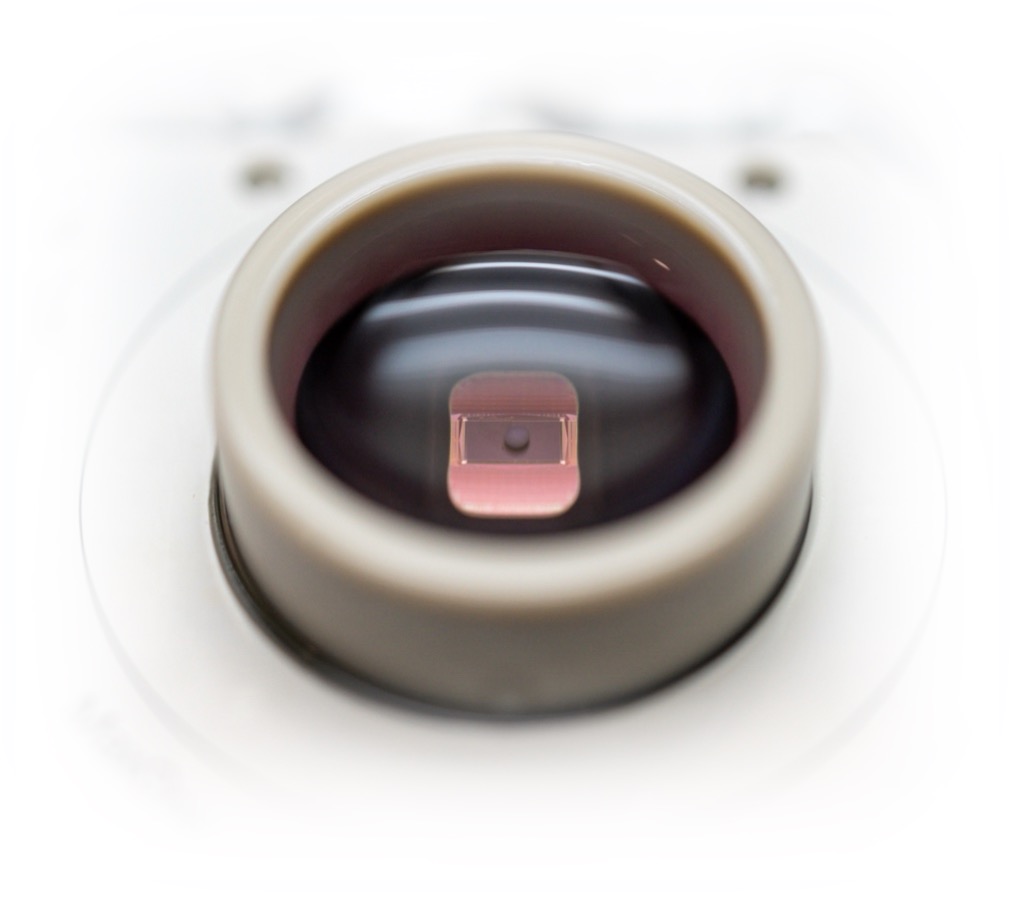

Furthermore, Ikeuchi envisions using artificial brain tissues such as organoids and connectoids to uncover the fundamental principles of brain function, and applying those insights to studies on the evolution of life and the development of advanced computing technologies. In fact, he is currently working to develop technologies that will enable brain organoids to perform computational tasks, effectively functioning as living computers.

Computer chip that makes use of brain organoids

Credit: Yoshiho Ikeuchi Laboratory (Created by Project Researcher Tomoya Duenki)

What challenges must be overcome to move toward such a future? Ikeuchi’s response was unexpected.

“Our current challenge is that we’re still acting as caretakers for the cells. At present, the most labor-intensive part of the process is cultivating the cells themselves. Organoids inevitably show variation, and we are still working through trial and error to determine the conditions that allow them to grow stably. Of course, there’s a certain satisfaction in the meticulous process of cultivating cells. But scientists can’t remain caretakers forever if we wish to take this research to the next level. Ideally, we should be able to delegate cell cultivation to robots so that researchers can devote their time and energy to the originally intended creative work—writing papers, developing new ideas, and pushing the boundaries of discovery.”

Just as the connectoid was born from the fusion of engineering and biology, the future of life science will likewise depend on the integration of entirely different disciplines. Ikeuchi emphasizes that understanding the brain’s complex functions will require the collective expertise of researchers across a wide range of fields.

“Actually, I have a secret ambition to one day rename this institute the Institute of Brain Industrial Science,” he says with a laugh. “Creating a brain will require working closely with people in fields like AI, electrical engineering, materials science, chemistry, and medicine. It will also be vitally important to build a strong, collaborative community among researchers. UTokyo-IIS has more than a hundred laboratories across a diverse range of disciplines. If we were to bring together everyone’s expertise to create a brain, I’m sure we could achieve something truly remarkable.”

Like brain organoids that extend their axons to connect with one another, Ikeuchi’s research, too, will continue to reach outward, forming new connections and opening doors to entirely new worlds. We eagerly await the day when another hidden facet of the brain’s mysteries comes to light.

“Complex activity and short-term plasticity of human cerebral organoids reciprocally connected with axons “, is published in Nature Communications volume 15, Article number: 2945 (2024) at DOI: 10.1038/s41467-024-46787-7

Related Link> Connecting lab-grown brain cells provides insight into how our own brains work

Featured Researcher

Yoshiho Ikeuchi

(Professor, Institute of Industrial Science, The University of Tokyo)

Special Field of Study: Biomolecular and Cellular Engineering

Comments

No comments yet.

Join by voting

How did you feel about the "Possible Future" depicted in this article? Vote on your expectations!

Please visit the laboratory website if you would like to learn more about this article.

Share