Unveiling the Hidden World of Nano-Materials

Exploring the true nature of atomic clusters comprised of several up to a few dozen atoms

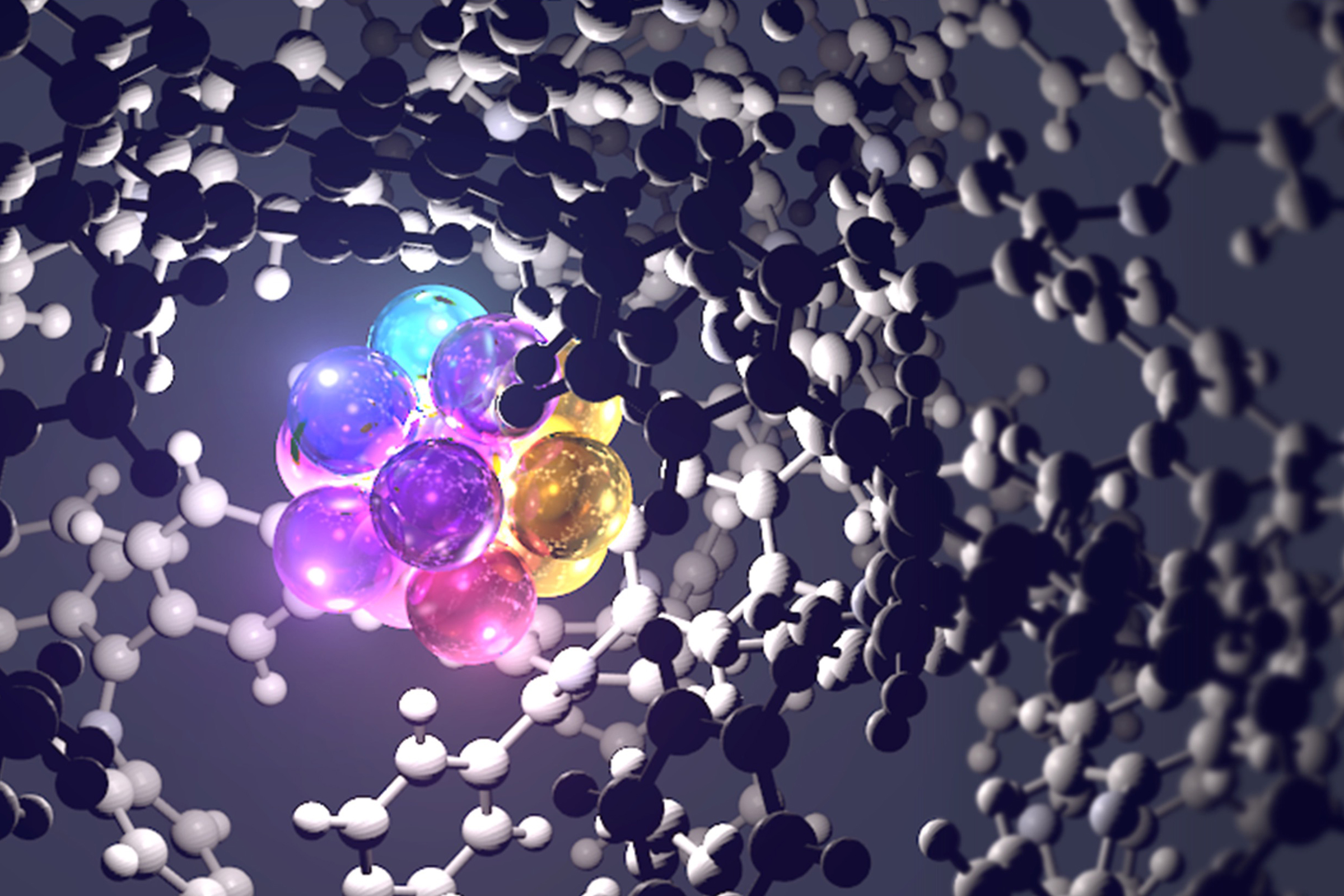

Research on nanoparticles has advanced rapidly since the 2000s. However, most studies to date have focused on particles 5 nanometers or larger in size. Against this backdrop, in recent years, increasing attention has been given to atomic clusters—structures approximately 1 nanometer in size, consisting of anywhere from several up to a few dozen atoms. Lecturer Takamasa Tsukamoto, at the Institute of Industrial Science, The University of Tokyo, is pioneering a groundbreaking method for synthesizing these atomic clusters, which hold untapped potential. At the same time, he is also working to identify the periodicity (i.e., the recurring regularity) of atomic clusters and delve deeper into their fundamental nature. We spoke with Tsukamoto to find out what has been discovered and what new possibilities lie ahead.

What are atomic clusters, with properties that change with the addition or subtraction of a single atom?

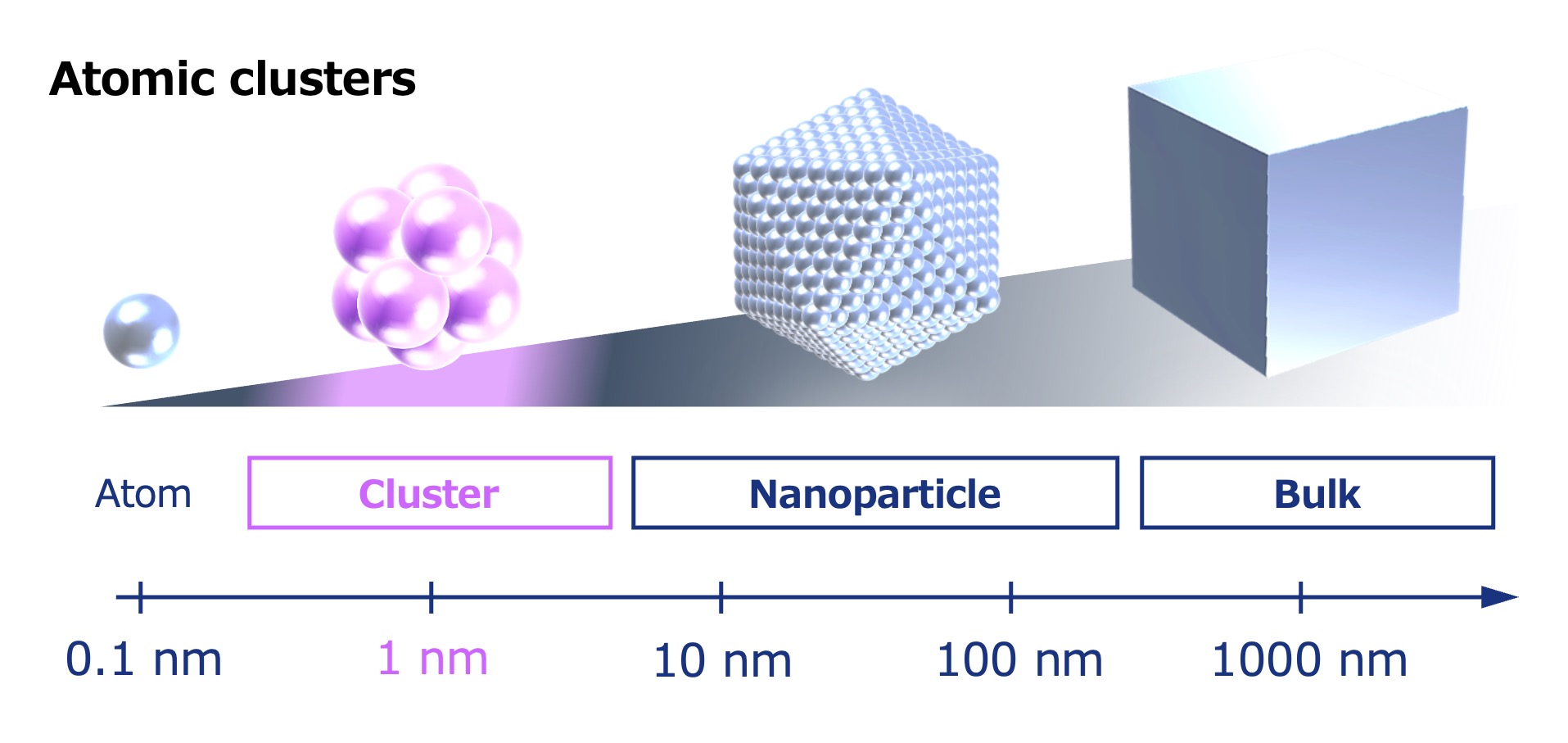

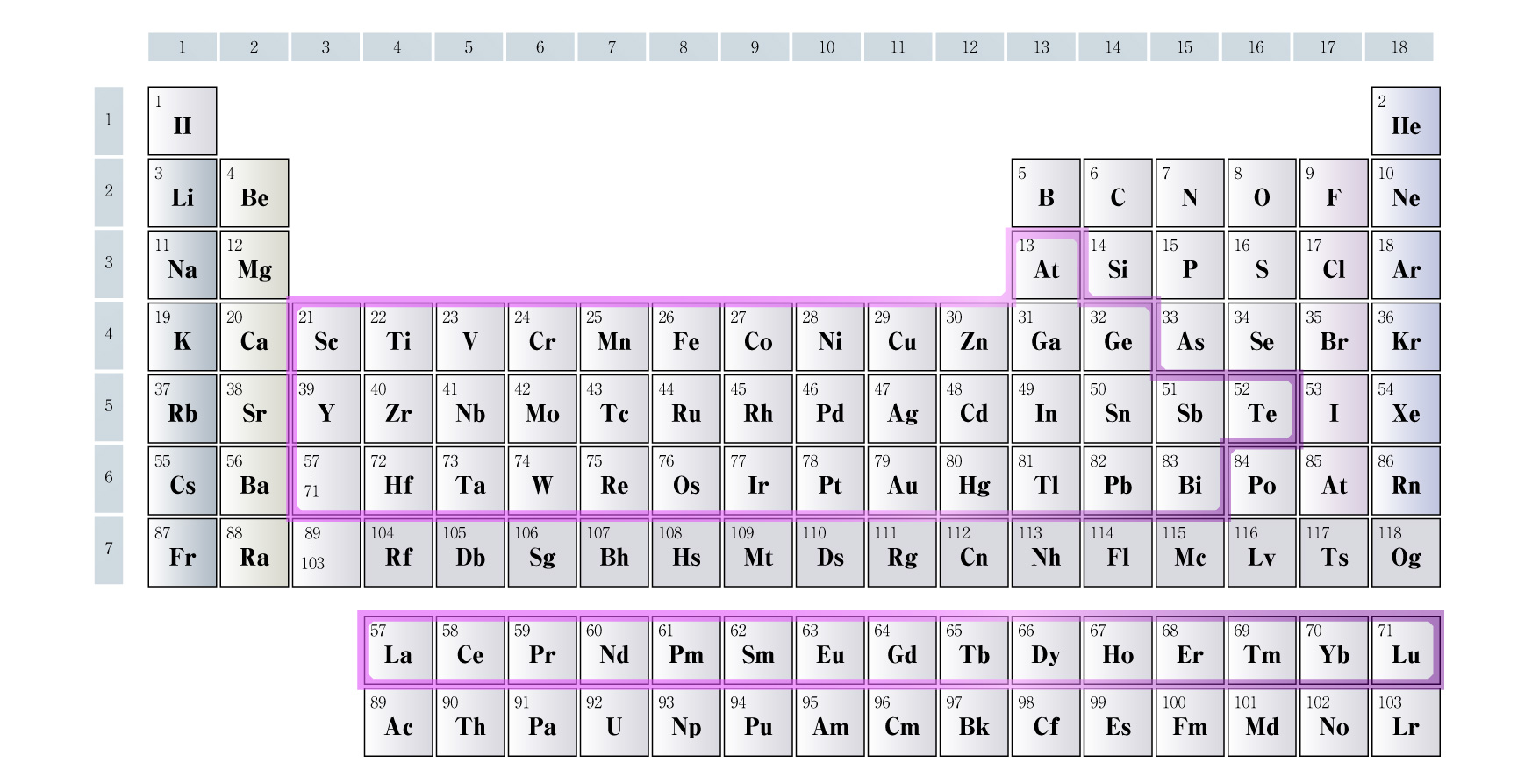

The term nanoparticle generally refers to particles ranging from 10 to 100 nanometers in size (1 nanometer = one-billionth of a meter). Atomic clusters (hereinafter simply referred to as “clusters”) are even smaller, at approximately 1 nanometer in size and composed of anywhere from several up to a few dozen atoms.

Atomic clusters are now attracting attention as they potentially hold the key to new materials with properties never before seen.

Image: Lecturer Tsukamoto Takamasa

Lecturer Tsukamoto, who has studied the topic for many years, said, “Due to the extremely small size of clusters and the fact that they are strongly influenced by quantum mechanics––namely, the quantum size effect––the addition or subtraction of even a single atom can lead to clusters displaying entirely different properties. For example, a cluster of 13 metal atoms and a cluster of 14 metal atoms will have completely different atomic arrangements, shapes, and internal electron states. This means that there is the possibility of generating a remarkably diverse range of properties by altering factors such as the number of atoms, type of element, atomic arrangement, and three-dimensional structure.”

Nanoparticles, which range in size from 2 to 100 nanometers and are composed of thousands to hundreds of millions of atoms, exhibit no great changes in their properties when increasing or decreasing the number of atoms by one. On the other hand, the addition or removal of a single atom can cause the properties of clusters, which are composed of anywhere from several up to a few dozen atoms, to undergo significant changes.

Image: Lecturer Tsukamoto Takamasa

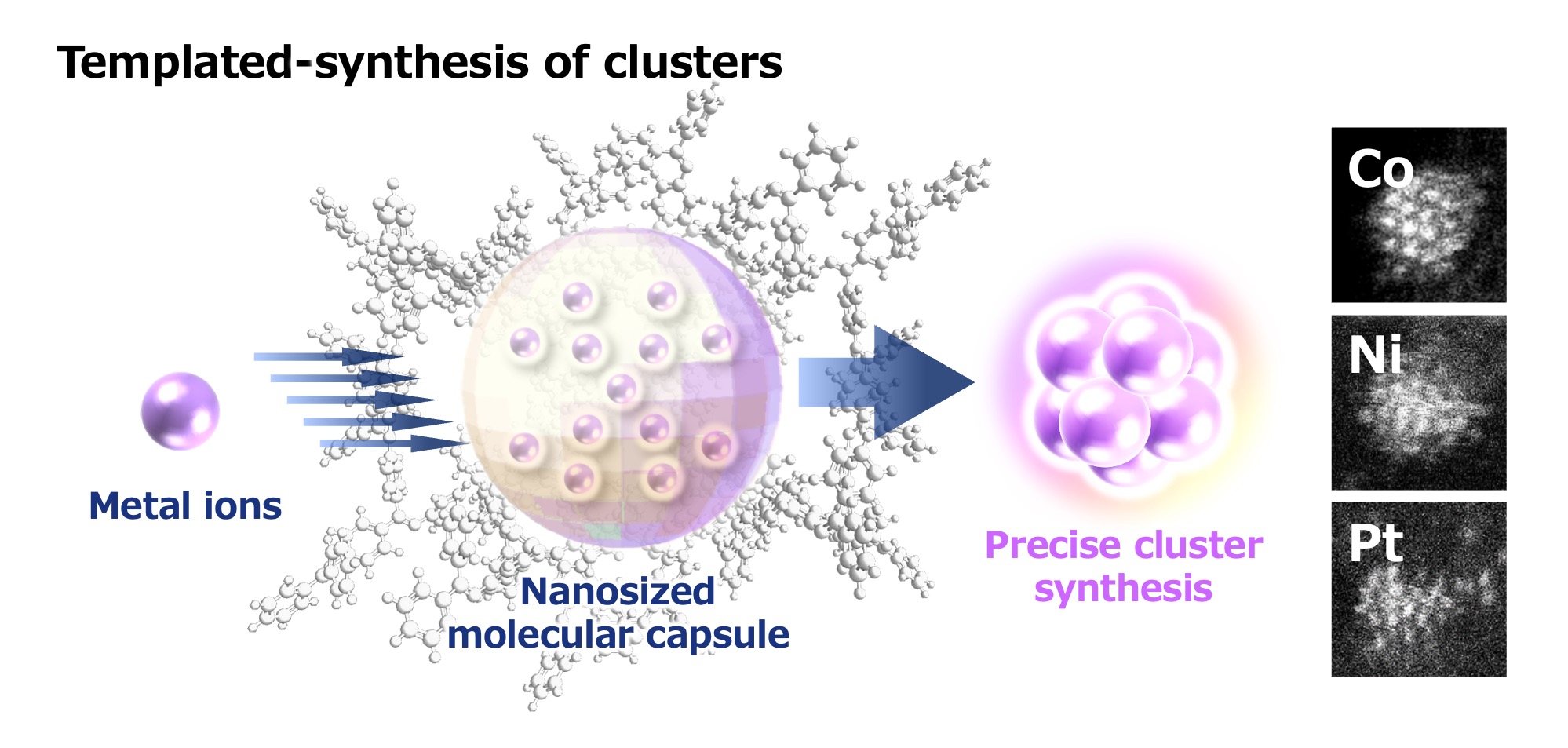

The template synthesis method, a versatile approach to atomic cluster synthesis

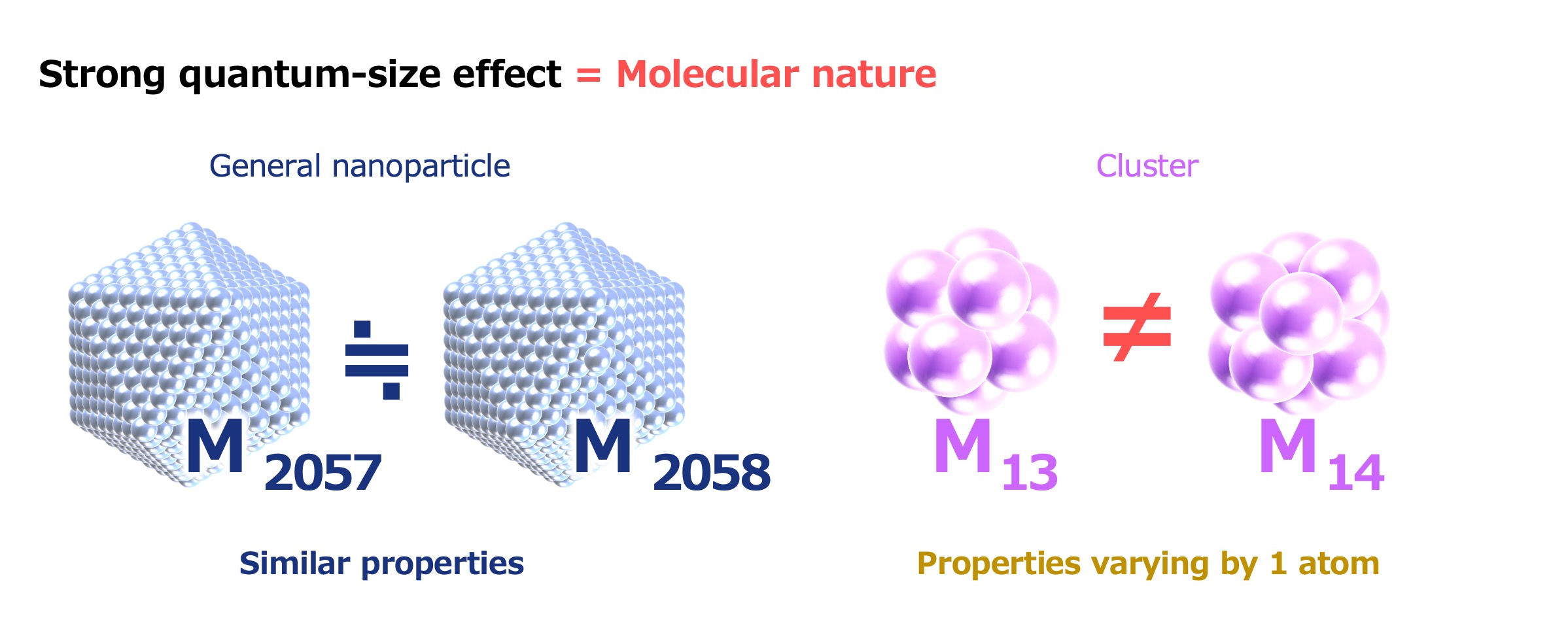

However, synthesizing clusters is challenging in that there is no versatile method for creating clusters that provides complete control over the type of element, number of atoms, and three-dimensional structure. That is why research in this field has remained stagnant. However, Tsukamoto remained dedicated to discovering a solution, leading to the development of a groundbreaking new method—the template synthesis method.

“Simply put, this method involves creating capsule-shaped macromolecules (organic molecules) for use as templates to synthesize clusters. First, we create organic molecular capsules that are designed to trap the desired number of metal ions at the desired locations, and the metal ions become enclosed within these. It is then possible to synthesize clusters by reducing these ions in order to convert them into metals.”

Schematic diagram of the template synthesis method. Metal salts (metal ions) are collected inside a dendritic polymer capsule and then reduced in order to synthesize clusters. Collecting a variety of metal salts also enables the synthesis of multi-element alloy clusters.

Image: Lecturer Tsukamoto Takamasa

Using this method, Tsukamoto has actually succeeded in synthesizing clusters composed of a single element for all metals from groups 3 to 16 on the periodic table. He noted that it was challenging to identify the optimal conditions (such as temperature) for encapsulating metal ions for each element. However, he demonstrated that, once the conditions are right, this method can be used to create clusters for a wide range of metals.

All metals from groups 3 to 16 on the periodic table

At the same time, an investigation into the functions and properties of the synthesized clusters revealed a variety of properties, including some that emit light and others that function as catalysts. This led Tsukamoto to explore whether he could theoretically elucidate how the functions and properties of these clusters relate to factors such as the type of element, number of atoms, and three-dimensional structure. Even slight differences in the number of atoms or three-dimensional structure can alter the properties of clusters, and if the underlying regularity governing these changes can be understood, it might become possible to design and synthesize clusters with precisely tailored properties.

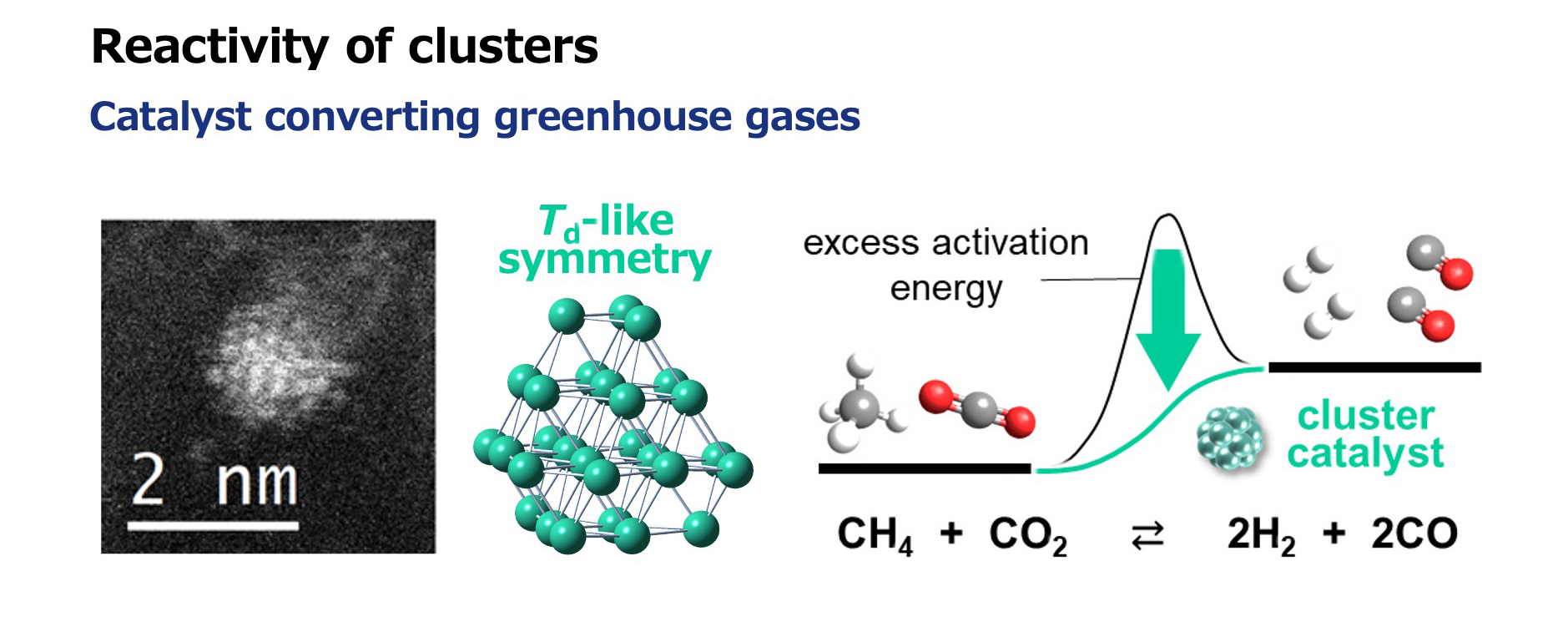

Tsukamoto also discovered clusters that function as catalysts in chemical reactions that convert greenhouse gases (such as carbon dioxide and methane) into hydrogen and other substances. He said, “These clusters are shaped like a tetrahedron (pyramid) with its top cut off. Previous studies had already established that solid surfaces with large sloped areas tend to function well as catalysts, so I synthesized a cluster with a structure missing that part, and it did indeed function as a catalyst.”

Image: Lecturer Tsukamoto Takamasa

In between experiments on synthesizing clusters, he also began researching to uncover the underlying theoretical principles. Although he initially began this research half for fun as a free study project to work on during breaks, over the course of several years of study, he identified a recurring regularity—or periodicity—between the geometric structures of clusters and their functions and properties.

Constructing a periodic table of nano-materials to classify clusters

The first step that Tsukamoto took in his theoretical research was to re-examine the general model of clusters.

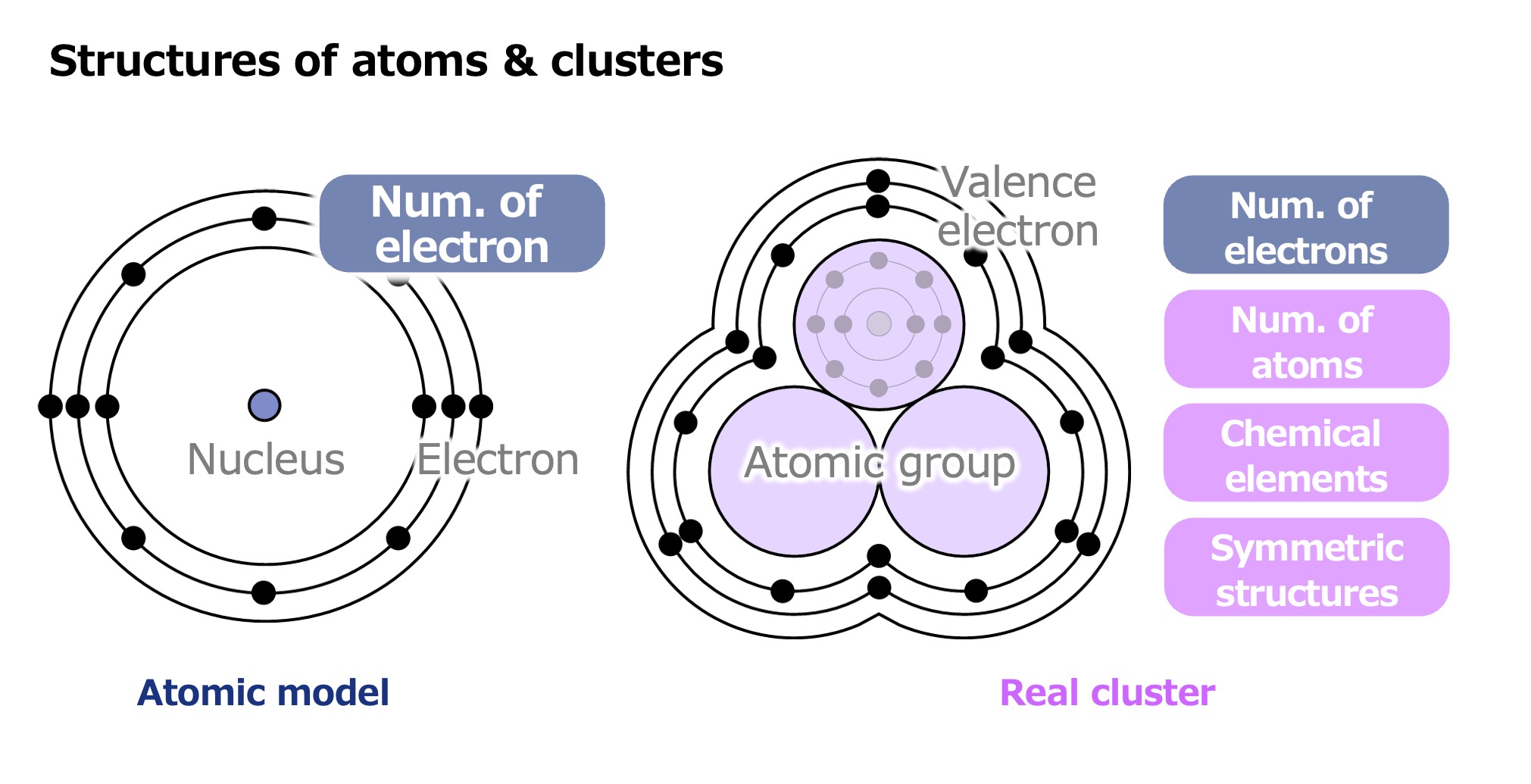

“The Jellium model, proposed in 1995, has been widely used as a framework for understanding clusters. This model treats a cluster as a single virtual sphere when calculating the distribution of electron orbits. However, this approach fails to explain why certain clusters are able to exist stably. This is likely because the sphere is only a rough approximation. So, I set out to develop a model that more closely reflects the actual structure of the particles.”

The Jellium model closely resembles the atomic model. It treats each cluster as a single virtual sphere, and posits that the total positive charge of the constituent atoms is evenly distributed throughout the sphere. In this model, the distribution of electron orbits is then calculated under the assumption that the electrons move within that range. From the orbital distribution, it is possible to predict how many atoms will be needed to form a stable cluster for a given element. However, there are some cases of stability that this model fails to explain. Therefore, in order to calculate the orbital distribution of electrons, Tsukamoto devised a model that more closely reflects the actual structure of the particles by taking the geometric symmetry of clusters into account.

Image: Lecturer Tsukamoto Takamasa

Tsukamoto applied both group theory and crystal field theory to develop a model that considers the actual shape of clusters (including variations such as regular tetrahedrons, regular octahedrons, and regular icosahedrons). He then used computer simulations to calculate the orbital distribution of electrons, and in the process, he discovered that each shape has a distinct pattern of electron arrangement. His results showed that this new model could explain cases that the Jellium model could not.

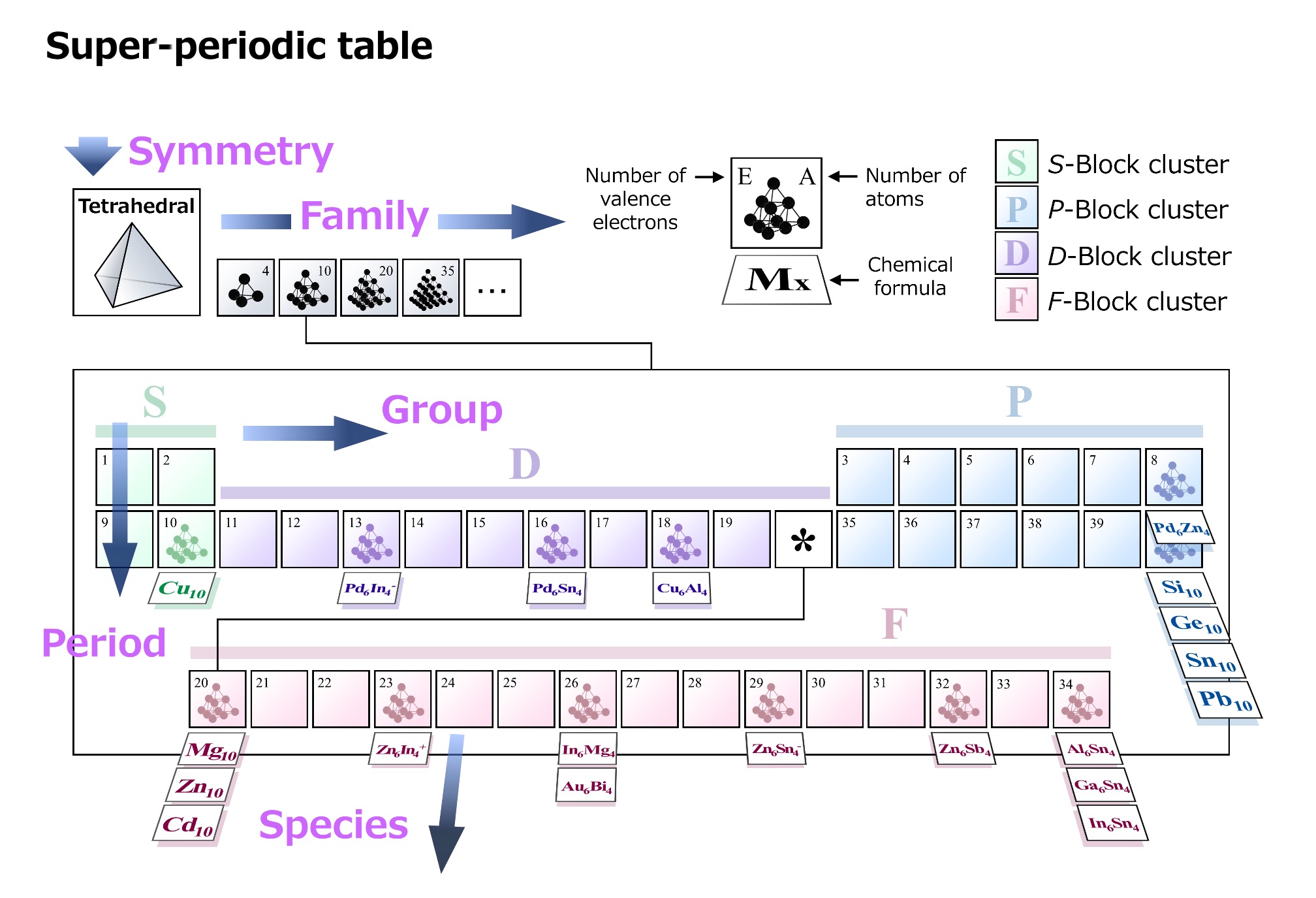

It was found that this new model, dubbed the symmetry-adapted orbital model, enables the prediction of cluster functions and properties based on factors such as the number and type of atoms and the shape of the cluster. Tsukamoto then developed a nano-material periodic table (super periodic table) that can be used to classify and search for clusters, in a manner similar to how the conventional periodic table of elements is used.

In addition to the conventional group and period axes, this periodic table of clusters includes the axes of family and species. These four axes enable clusters to be distinguished by the number of atoms, number of electrons, and type of element, which in turn makes it possible to predict a cluster’s functions and properties based on its position within the table. Following this new classification index facilitates discussion by integrating the various known cluster materials into a single table, and it is now possible to predict in advance how many atoms of which elements and in what ratios are needed to create clusters with specific functions.

Image: Lecturer Tsukamoto Takamasa

“With this periodic table, it is theoretically possible to predict––for example––that even non-magnetic elements, such as silver and aluminum, will exhibit magnetism if a specific number of atoms are assembled into a cluster with a certain shape. Whether or not they can actually be created is another matter, but using this periodic table as a guide makes it possible to envision a future path toward developing new materials that challenge conventional wisdom, such as creating super-lightweight magnets from aluminum.”

A unique outlook born from the pursuit of art

As another potential application of this periodic table, Tsukamoto envisions someday being able to identify higher-order molecules composed of clusters, which could be seen as higher-order elements. Through his theoretical research, Tsukamoto also predicted the existence of an entirely new class of materials known as super-degenerate nanomaterials, which exhibit a higher degree of symmetry than spheres. He further revealed that the advanced symmetries that underlie this group of materials are related to the mathematics used in elementary particle physics and similar fields.

Tsukamoto’s research hints at the possibility of a new, undiscovered realm of matter. Will we be able to continue opening the new doors that we encounter in this new frontier? Exciting developments lie ahead.

“This research has been uncovering, one after the other, phenomena that textbooks would deem impossible. Ordinarily, we base studies and research on the assumption that the textbooks are correct. However, this research has shown us that this is not always the case. I am committed to developing this research even further—into something that adds new pages to the textbooks.”

Comments

No comments yet.

Join by voting

How did you feel about the "Possible Future" depicted in this article? Vote on your expectations!

Please visit the laboratory website if you would like to learn more about this article.

Share